Insights from experiment on self with real-time data

Evidence from the literature suggests that physical activity improves emotional regulation, and can prevent and help manage symptoms of depression. I conducted a four-day experiment where I logged in my physical activity and emotions to understand the impact being physically active on my ability to regulate my emotions better.

Background

The year before COVID-lockdown, I had moved to the US, a country I was new to. When COVID hit and the lockdown began, I was in my one-bedroom apartment in the new city trying to figure things out.

During that time I put together this experiment to help me keep track of my physical activity and emotions.

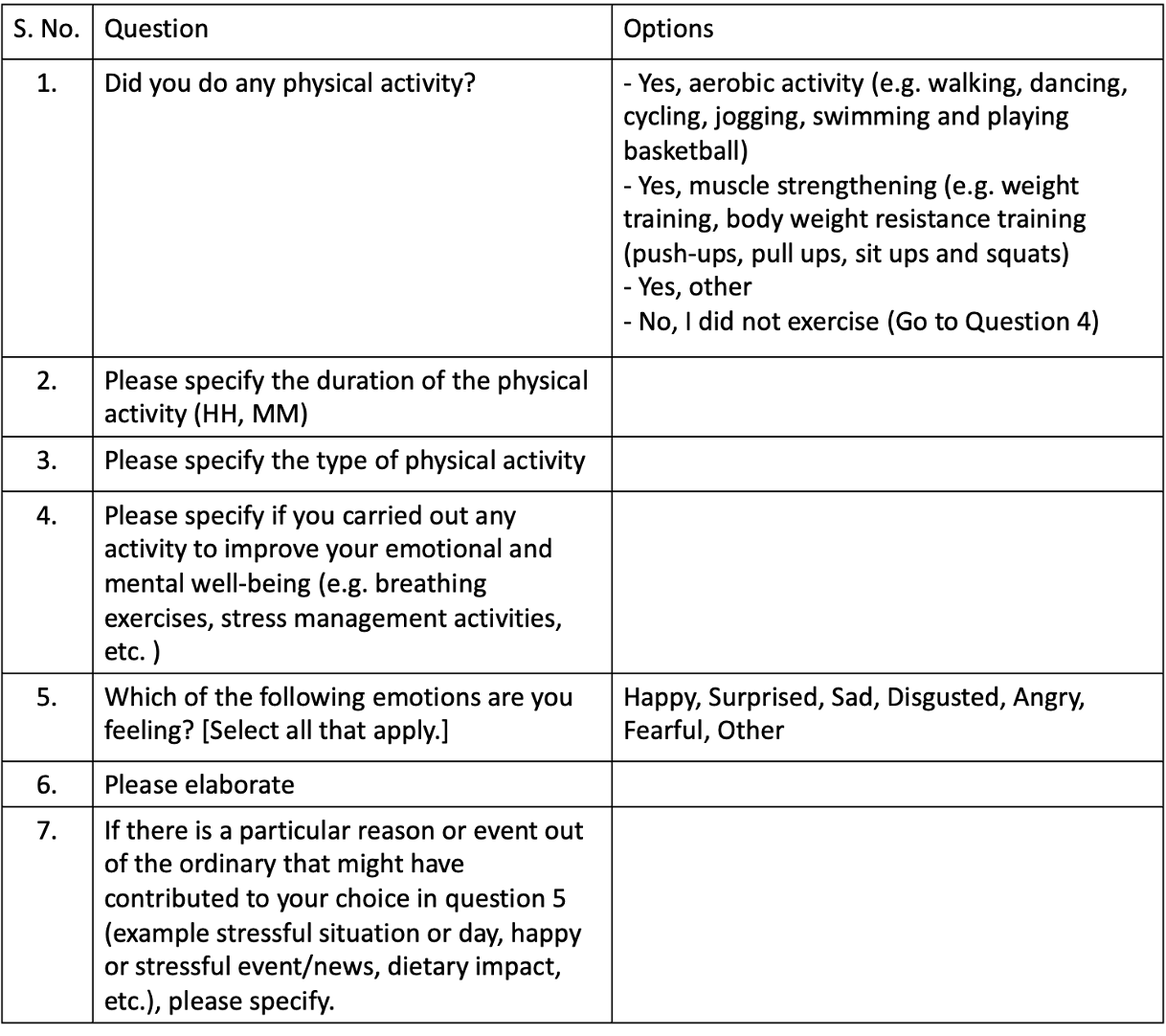

I used the PIEL app to put together the survey questionnaire in my phone and prompt me to complete it three times a day – morning, afternoon, and evening.

The survey questions captured physical activity, self-care behaviours, emotions (drawn from Ekman’s basic emotions – anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise), and contextual triggers, treating affect as dynamic and tied to daily routines under real stressors (COVID-19 lockdown, family conflict, work deadlines).

Here is the list of Qs on the survey:

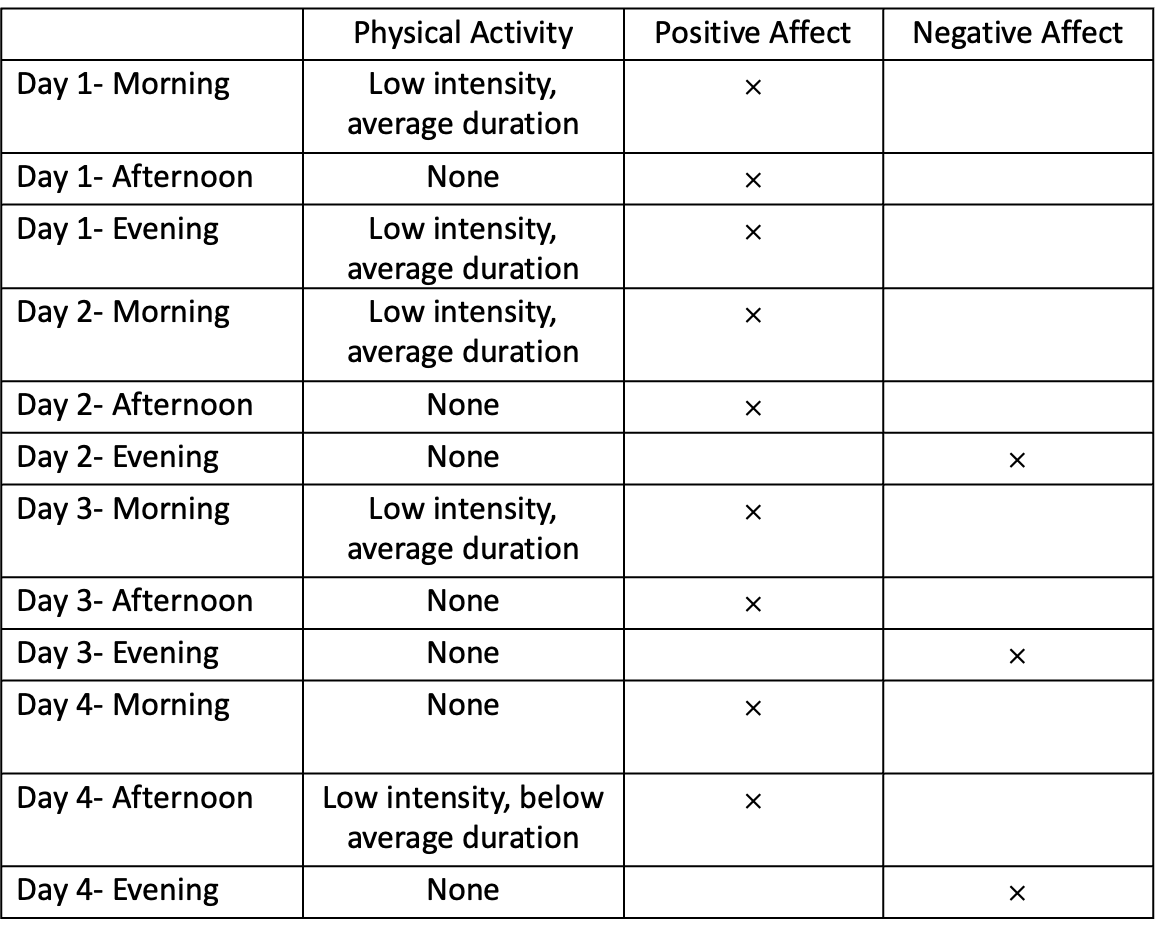

I filled in the survey three times a day for four days – morning ~11:50am, afternoon ~5pm, evening ~10pm, and used the Apple Watch sensor data for activity verification.

Physical activity was mostly low-intensity with an average duration of ~20–40 minutes, with mainly yoga in the mornings and walking in the evenings; intensity followed US Department of Health guidelines, and used the data from sensors to confirm my self-reports (e.g., steps, distance).

My experiences

Morning yoga and breathing exercises (30–40 minutes) consistently triggered positive affect—calm and satisfied on Day 1, calm but slightly stressed on Day 2 (due to deadline), satisfied and happy on Day 3—carrying into afternoons as productive, ’emotional but motivated’, or relaxed. This felt like a “reset”: disrupted lockdown routine inertia, grounded me amid family stress, and buffered work worries.

Afternoons without exercise stayed positive via carryover from mornings or other activities (spiritual audiobooks, games), but evenings without activity often shifted negative: tearful/emotionally stressful (Day 2), scared about work (Day 3), worried/sad (Day 4 evening). Evening walking (50 minutes Day 1) sustained calm/happy emotions into night, suggesting time-limited effects—positive boosts faded without reinforcement.

Day 4’s partial lockdown lift added hopefulness in the morning and afternoon (with a brief 10-min walk in the afternoon), but evening negative affect returned in absence of activity, highlighting the role of external events as well as exercise’s buffering potential. Baseline moderate stress (stress score due to work 4 to 5 on a scale of 10, and stress score due to personal reasons 6 to 7) and disrupted gym routine also amplified fluctuations in emotional affect, but physical activity was reliably linked to more positive, regulated states.

See the summary table below:

Insights

The data suggests that physical activity, even low-intensity, correlates with better emotional regulation—morning sessions stabilizing the day, evening ones preventing downturns—under stress. It also illustrates how collecting data in real-time can add value for personal insight, especially for affect which can shift over short durations of time.