D for Disconnect and Detach

Recovering from work related stress on a regular basis is important as it enables us to stay healthy, engaged, and energetic, as well as promotes resilience in the long run. And recovery occurs when no further demands are made on the functional systems that were called upon during work, including, but not limited to, our minds.

There are multiple ways in which individuals can recover from work. Following are some of the activities that allow individuals to divert their minds away from work and recover:

- psychologically detaching and disengaging from work

- pursuing relaxation-oriented activities such mindfulness

- developing skills in an outside work activity of interest such as playing an instrument

- participating in group activities and shared experiences

- activities that add meaning and purpose to one’s life such as volunteering, running, storytelling, etc.

- other activities that promote a sense of control over future

Among these, psychological detachment and mindfulness are particularly effective for reducing stress and helping our minds recover.

What is Psychological Detachment?

Psychological detachment refers to refraining from work related activities and mentally disengaging from work during time off, and as per research, and is one of the most efficient ways to recover from work related stressors.

We are often easily able to disconnect, but mentally detaching and disengaging is the next step and takes additional effort. Diversionary activities are useful aids that can help us detach.

Diversions such as helping with one’s children’s school problems, or the other recovery promoting activities mentioned above, can help us disengage from work by letting our minds be occupied with other non-work thoughts. Detachment can also be achieved by being in a meditative state of thinking ‘nothing’, although it may take more practice to achieve this state.

In addition to effectively recovering from stressors, research has shown that individuals who are able to detach from work during non-work hours see better outcomes at work as a result.

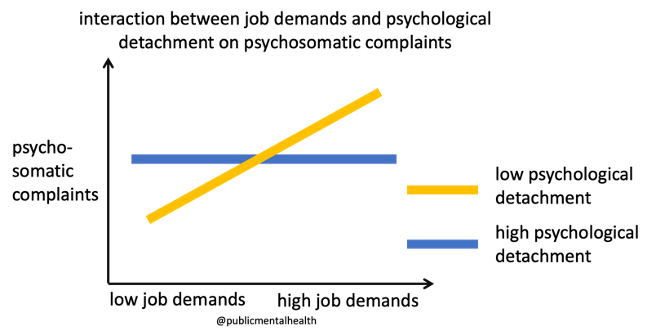

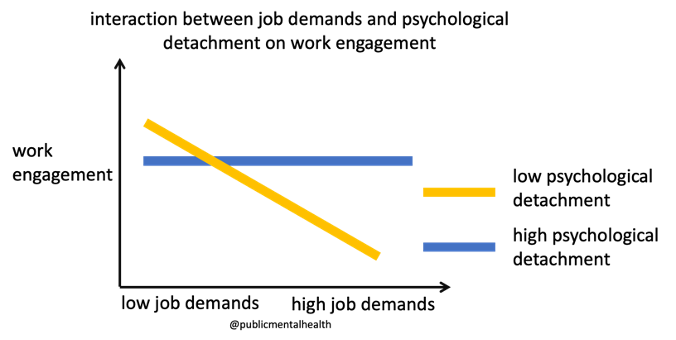

For example, a study found that individuals who are able practice high levels of detachment, can improve their resilience and develop a level of immunity to stressors such as increase in job demands at workplace. See below for the interaction between job demands and level of detachment on psychosomatic complaints and work engagement.

On the other hand, low levels of detachment can lead to high strain levels and contribute to prolonged activation of specific functional systems, which eventually impact work engagement over time and increase psychosomatic complaints among individuals.

We can learn to detach and disengage from work by actively practicing the art of ‘letting go’ and diverting our mind by ‘hanging on’ to recovery-focused activities.

Some of the factors that influence the type of recovery activity we choose include our age, personality traits, lifestyle, attitude towards work, etc. Spend some time in discovering the activities that work for you and help you detach, and make them an integral part of your routine.

References:

- Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 15(3), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor‐detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36.

-

Sonnentag, S., Binnewies, C., & Mojza, E. J. (2010). Staying well and engaged when demands are high: The role of psychological detachment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 965–976. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020032

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204